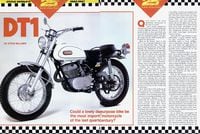

The success of Yamaha's DT-1 250 two-stroke enduro of 1968 was the spearhead of Japan's invasion of off-road motorcycle sport. Light, maneuverable two-stroke off-road bikes already existed, but they came from low-production specialist producers like Greeves, Bultaco, and CZ. Yamaha industrialized off-road, bringing reliable engineered bikes to a wide public.

Four-strokes dominate off-road today but many still fondly recall the days when it cost under $100 and thirty minutes’ work to get running again after a two-stroke seizure. If the parts of your high-revving four-stroke MXer all crowd into the same space at the same time you’d better have another $4000 engine ready to slot in or your day at the races is done. Two-strokes were stone simple, with no valves other than the piston itself, covering and uncovering ports in the cylinder walls as it slid up and down.

DT-1's cylinder porting was made intentionally conservative to give it a wide pulling range. Five speeds were adequate. Exhaust opened a late, late 98-degrees after top center, with the four transfer ports opening barely 22 degrees later. The period between exhaust and transfer opening is called 'blowdown' because this is the time available in which exhaust pressure in the cylinder must fall below the crankcase pressure that will push fresh charge into the cylinder through the four transfers. On the simplest of engines, such as BSA 125 'Bantam' or Harley's 'Hummer' of the late 1940s, blowdown was really short – 15 degrees – to go with peak power at 4500-rpm. DT-1's peak came at 6000, requiring 22 degrees blowdown timing. A racing engine would require more yet – 30 – 35 degrees.

Yamaha’s Grand Prix road racing engines 1959-68 all had single exhaust ports and three transfers (a big one on either side of the exhaust and a single upward-aimed “finger port” opposite the exhaust). Intake was by rotary disc valve, with a carburetor mounted on the side of the crankcase. You can see the heritage of that development in DT-1’s four transfer ports. The larger pair, on either side of the exhaust, are carried over from Yamaha’s Grand Prix past. The smaller pair – a little more than half their width – represent the coming era of 4, 5, 6, and even 7 transfers.

Before the late 1950s off-road was as four-stroke dominated as it is today. The usual tools were a 300-pound BSA Gold Star powered by a 500-cc four-stroke pushrod single (about 10% of its weight was crankshaft!), or a "bearing-thrasher" Triumph Cub, modified to the max. But by 1955 two-strokes were undergoing a horsepower revolution, so a two-stroke revolution was about to break out in several places at once.

When a European motocross championship for 250 machines began in 1957 it was won by Fritz Betzelbacher on a Maico two-stroke. Two-stroke engines were light, so their chassis and other cycle parts could also be light. Husqvarna’s ‘Silverpilen’ 250 weighed just 165-lb. The English-made Greeves, powered by a none-too-sophisticated Villiers two-stroke, was just the tool for Dave Bickers, winning back-to-back European MX titles in 1960-’61. Sammy Miller, who had won trials titles on Ariel four-strokes, won the Scottish Six-Days Trial in 1965 on an unknown featherweight Spanish two-stroke – a Bultaco.

Motocrossing 1950s-technology four-strokes had been like trying to dance in weighted Navy diver’s shoes, but the light new two-strokes were PF Flyers.

In the spring of 1963 I could recognize a Greeves 250 start-up from the flat “BAP-BAP-PA-BAP” emitted from its open-ended “blooey pipe”. Didn’t matter that its engine tech was crude and its transfer ports resembled casting flaws; it was so light that modest power made it successful. European makes wasted no time in adopting German-style “gegenkonus” (counter-cone) two-stroke pipes, terminating not in an open megaphone but in a cone converging to a small outlet pipe or “stinger”.

Edison Dye saw the possibilities and saw to it that this new European sport of motocross, plus its star riders and the bikes they rode, came to the USA. In those early days, the dealerships for these hot new brands were in dirt-floored sheds, run by enthusiasts who had become dealers mainly to get parts at cost. They served a tight in-group of riders who all knew each other, competed weekly, and serviced their own equipment.

Just as fashion scouts scope out teen habitats for emerging clothing trends, Yamaha product planners could see an off-road market taking form. Motocross, enduro, and trail riding were attractive activities, but how do you get “in”? How do you summon a replacement CZ rod set from Czechoslovakia? Yamaha made it easy; go to the Yamaha dealer and buy a new DT-1 250. It was competent on the road and had a measure of off-road capability that was easily enhanced by modification. The parts were durable and cheap, and service procedures were easy.

The DT-1 had dimensions of 70 x 64 and was a dead-simple four-transfer piston-port two-stroke single with ‘Autolube’, which made mixing oil into gas unnecessary. Power is quoted as 18 – plenty to move its comfortably-under-300-lb weight.

In 1972 DT250 was given reed intake in place of piston-port. The piston-port engine had been stuck at a compromise 76/76 open/close timing, but reed valves stayed open as long as there was airflow trying to push its way in. This allowed engines to make more power without too much sacrifice of powerband. Flexible thin metal flapper valves, which we call reeds valves because of their resemblance to saxophone reeds, were for years used as intake valves for compressors. When Carl Kiekhaefer needed to develop simple, reliable small two-strokes during WW II, he adopted reed intake (his company became the outboard maker, Mercury Marine). Rumor has it that Dale Herbrandson had something to do with Yamaha’s introduction to reed valves but I’ve never been able to confirm it.

The suspension of the original DT-1 was conventional, with twin rear shocks giving the usual 3 inches of travel, but soon it was discovered that riders could cover rough terrain faster with longer-travel suspension. In 1973 Yamaha for its factory MX machine had adopted single-shock, long-travel rear suspension which it called “Monoshock”, and by 1975 the production MXer YZ250 (with original DT-1 bore and stroke) was so equipped.

Yamaha went on to produce DTs in a range of displacements and, with continuous development, had a major long-lasting sales success on their hands, moving hundreds of thousands of off-road motorcycles.

/cloudfront-us-east-1.images.arcpublishing.com/octane/N575KB7BDZDPPJBRLZRG2ANHKI.jpg)

/cloudfront-us-east-1.images.arcpublishing.com/octane/T77HXRXV4NGKDNZODMSEIBRXPE.jpg)

/cloudfront-us-east-1.images.arcpublishing.com/octane/NKMM7V2P3BCSXAV6J56FKK67OU.jpg)

/cloudfront-us-east-1.images.arcpublishing.com/octane/SWQRQV27DNFA7LXGFI7FNFNGOQ.jpg)

/cloudfront-us-east-1.images.arcpublishing.com/octane/GYEXUJBV5JGQLLZNXO7KRVSTEY.jpg)

/cloudfront-us-east-1.images.arcpublishing.com/octane/MCWUSJJVJVG45P7QQG3WOXZR54.jpg)

/cloudfront-us-east-1.images.arcpublishing.com/octane/AJ4EFPH2CRDURDAB5LPEA2V2NE.jpg)

/cloudfront-us-east-1.images.arcpublishing.com/octane/LSDHIL22SZAFFPYLKP5ZXLJSIY.jpg)

/cloudfront-us-east-1.images.arcpublishing.com/octane/SH46HIOX4RELXLXF6AE3SFGH4A.jpg)

/cloudfront-us-east-1.images.arcpublishing.com/octane/JUZ52WFWLJGMNH7PGZNOKP3MUY.jpg)